May 31, 2008

*Feeling Bad-A** Quote

"Death had to take him sleeping. For if [Theodore] Roosevelt had been awake, there would have been a fight."--Thomas Marshall

May 26, 2008

*Superstitions: Rabbits' Feet

Carrying a hare's or rabbit's foot for medicinal purposes predates carrying one for luck by nearly a thousand years.

The feet were supposed cures for anything from arthritis to colic to cramps. Pliny (Elder) wrote, "Gouty pains are alleviated by a hare’s foot, cut off from the living animal, if the patient carries it about continuously on the person.”

The transition from medical charm to lucky charm apparently occurred in the United States, with Great Britain and other countries borrowing the superstition from Americans in the 19th and 20th centuries.

So why would a rabbit's foot be lucky? It seems that the idea comes from the rabbits' fertility, which translates into prosperity and abundance for the owner of a rabbit's foot.

Reference: Most of the material from this post was found in David Pickering's Dictionary of Superstitions and Steve Roud's The Penguin Guide to the Superstitions of Britain and Ireland.

May 21, 2008

*Foot, Spirits Broken

I don't know how much more of this I can take.

Blogging in all likelihood suspended until after Memorial Day.

May 19, 2008

Feeling Wilde

"In America the President reigns for four years, and Journalism governs forever and ever." -Oscar Wilde

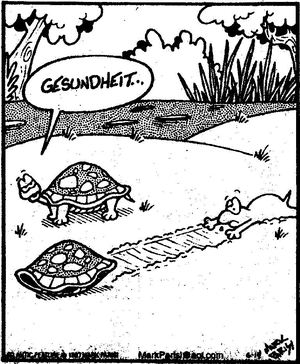

*Superstitions: Gesundheit!

Saying “God bless you” or “Gesundheit” in response to someone’s sneezing is extremely common throughout Europe and America. “Gesundheit” simply means “health”, and a post-sneeze wish for good health is found even in the writings of Pliny the Elder.

This early mention of the practice disproves the widespread belief that “God bless you” originated during the 17th Century Plague, when sneezing was supposedly a symptom. The earliest reference in England dates to 1483; also well before the Great Plague.

Superstitions around sneezing probably originated with the earliest people, who may have thought this little explosion in the head was some sort of sign from the gods. Some people still believe that sneezing leads to a temporary deprivation of the soul, with “God bless you” returning the soul to the body.

Reference: Most of the material from this post was found in David Pickering's Dictionary of Superstitions and Steve Roud's The Penguin guide to the superstitions of Britain and Ireland.

May 16, 2008

*Get Your Flashlights...

...it's time for a ghost story...

Bloody Mary

Bloody Mary

Bloody Mary

Bloody Mary

Bloody Mary

Bloody Mary

Bloody Mary

Bloody Mary

Bloody Mary

Bloody Mary

Bloody Mary

Bloody Mary

Bloody Mar-- *erk*

May 14, 2008

Testing Your Devotion I'll Give You a Topic

It's been many moons since I've given you a topic. So here's one:

Corndogs. Tasty food-on-a-stick, or unholy abomination?

Discuss.

May 12, 2008

*I'm Generally a Private Person

Which is why I'm irritated my life story is being made into a movie.

*Superstitions: Crossing Your Fingers

Crossing your fingers can give you good luck, ward off bad luck (like, say, when you have to walk under a ladder), and protect you from the consequences of a lie.

This practice is seen in America, Britain, and some parts of Scandinavia. The earliest reference found dates only from 1890, so it is surprisingly new. Before this, it was more common to clench the thumb with the fingers

So why cross your fingers at all? Once again, we can look to Christianity for the origins of this one: some people believe crossing your fingers makes the sign of the crucifix, which of course has the power to ward off evil.

Reference: Most of the material from this post was found in David Pickering's Dictionary of Superstitions and Steve Roud's The Penguin Guide to the Superstitions of Britain and Ireland.

May 07, 2008

See That Description to the Right?

The two parts excuses for not blogging bit?

Yep.

Normally there'd be an "Ask Jen" post here, and Shank did send in a rather long-winded question about an uncle and a hippie commune or something, but I didn't have time to give it my full attention.

So that'll probably be showing up next Wednesday, if I haven't keeled over from an enlarged heart from all the caffeine I'm ingesting in order to not sleep and therefore have time for completing the 9000 things I have due this week.

But there will be a Lyrical Pursuit post tomorrow because I scheduled that ahead of time, so you have that to look forward to.

So there ya go.

May 05, 2008

No Kidding

I have a reputation in my family (okay, everywhere) for being a tattle-tale. As I have explained to my sibs, this is because when we were kids and they did something wrong and I knew about it, I'd get in trouble too.

Eldest children have stricter parents.

The study showed that older siblings were much less likely to drop out of school or, in the case of girls, get pregnant, than the youngest in the family, perhaps because they’ve had a lifetime of being held to higher standards.

. . . .

“When a job needs to get done, it’s the habit of the parent to call on the first-born, because they’re the most reliable and conscientious,” Leman says.

I still get "projects" from my parents when they want something. Want Santa and his elves in your front yard at Christmas? Jennifer will paint them. I like doing that kind of stuff for them, but the other kids never get those calls.

*Superstitions: Walking Under Ladders

Cross-posted at DDBBG.

The superstition that walking under ladders is bad luck is fairly widespread. In America and Europe, this belief originated around the late 1700s.

There are a few theories as to the original thought behind this superstition. The first is that a ladder leaning against a wall forms a triangle--or trinity--with the ground. Walking through this triangle is disrespectful to God and may show your sympathy to the Devil.

Alternatively, any ladder can represent the ladder used to remove Jesus from the Cross, under which the Devil lurks. You don’t want to go where the Devil hangs out, now do you?

Whatever the origin of the superstition, there is a practical reason not to walk under ladders: you might get hit by something falling from above.

Reference: Most of the material from this post was found in David Pickering's Dictionary of Superstitions and Steve Roud's The Penguin Guide to the Superstitions of Britain and Ireland.

May 02, 2008

Recalling the Life of Leoba

In studying History, students are expected to look critically at the sources they use. This is my slightly edited critique of a source I had to read for a course on Medieval Women. The source was Rudolf of Fuldam's Life of Leoba.

Saint Leoba was a nun who lived during the 8th century and participated in missionary work with Saint Boniface in Germany. The story of her life was written by the monk Rudolf of Fuldam sometime around 836, about 57 years after Leoba’s death.

Rudolf wrote about Leoba’s life supposedly so that other pious women could emulate her. He dedicated the story to Hadamout, another nun, “to read with pleasure and imitate with profit.” However, the story was written at the behest of Rhabamus Marcus on the occasion of the movement and reinterment of Leoba’s relics. The true purpose in writing the account of Leoba’s life was to document her saintly status and cement her holiness in the historical record.

Rudolf wrote about Leoba for the current and future generations of Christian faithful, and he certainly thought of the women in particular. He recounted Leoba’s many virtues clearly so that they could be celebrated and copied by other women. Her behaviors of moderation, in particular, were mentioned more than once. She limited her quantities of food and drink to just enough to sustain health. She emulated her fellow nuns; taking the best virtue of each and practicing it herself, so that she embodied all the virtues that were wanted in a pious Christian woman in her lifetime. These were all qualities one would expect from a saint, as well.

Another quality expected from a saint is a life seemingly destined for holiness. Leoba’s mother reportedly had a dream or vision before her birth, foretelling Leoba’s fate. The mother had been unable to have children, but after she promised God that her child would be brought up in His service, she was able to conceive. Later, Leoba had her own dream or vision which was interpreted to mean she would spread God’s word and wisdom near and far. Rudolf demonstrated through his account of Leoba’s life that both of these prophecies came true, and this helped to further cement Leoba as a proper saint.

One can not be a saint without miracles, and Leoba had several miracles attributed to her during her life. Rudolf recalled four of these miracles through information gathered from the memoirs of those who actually knew Leoba. His main sources of information were four nuns who were Leoba’s contemporaries. Unfortunately, Rudolf could not read their memoirs directly, for they left none. Instead, a monk or priest named Mago wrote down the nuns’ recollections. This source is problematic for historians because Mago did not sit with each nun and transcribe their conversation. Rather, he wrote garbled shorthand notes during their group conversations.

Another problem with Rudolf’s sources arises when Rudolf mentioned other men who wrote about Leoba based on their own conversations with the four nuns, but did not see fit to actually name any of those men. Rudolf wrote that, “there should be no doubt in the minds of the faithful about the veracity of the statements made in this book, since they are shown to be true both by the blameless character of those who relate them and by the miracles which are frequently performed at the shrine of the saint.” The faithful may have no problem accepting the story at face value, but the rest of us wonder how we can substantiate the “blameless character” of men who remain unnamed. Rudolf’s intention in disclosing his sources was presumably to establish the infallibility of the information, although to a critical eye it fails to do this.

After recounting a miracle of a wicked woman who confessed to killing her baby as a direct result of Leoba’s prayers, there is an interesting passage in Rudolf’s narrative. He wrote, “Even before this God had performed many miracles through Leoba, but they had been kept secret. This one was her first in Germany and, because it was done in public, it came to the ears of everyone.” What is interesting about this is that he glossed over her supposed “many miracles”, and it is also amazing that miracles would be kept a secret. One wonders why the Church would conceal the glory of God’s work, when it could help other men and women find the light.

The next miracle recounted by Rudolf involved a fire in the village. Leoba put blessed salt in the water and the water put out the fire “as if a flood had fallen from the skies.” This miracle seems like it should have been credited to St. Boniface rather than Leoba, as it was Boniface who blessed the salt. Why water putting out fire was a miracle is a little muddled in this text, because Rudolf did not offer any details about the wonder of it beyond what is quoted above. Rudolf’s intended audience, however, would not be so critical. They would already believe, and this account of Leoba’s miracle would further strengthen her status as a saintly and holy woman.

The remaining two miracles recounted by Rudolf showed the power of Leoba’s relics. This was the only instance in Rudolf’s account that came from a reasonably reliable source, as it was Rudolf himself who witnessed these two events. It was the only first-hand account, as well as the only source actually named besides Mago.

Leoba did become a saint, and Rudolf’s account may have helped her in the canonization process. He included the information that would be needed to cement Leoba as a truly holy woman. She was a virgin, she embodied all the ideals of a Christian woman, God performed His works through her in the form of miracles, and she did God’s work as a nun and an abbess. She was extraordinary in that she traveled with Boniface to head up the new community of nuns he established in Germany. She was extraordinary in that she did not display a few ideal character traits, but all of them. Rudolf painted a picture of her as the flawless model that all Christian women should aspire to become. His main purpose was to prove her worthy of the title of “Saint”, and the side effect was that he made an example for Christian women everywhere.

Reference: the only source used in this post is Rudolf of Fuldam's Life of Leoba.

May 01, 2008

It's a New Thing--UPDATED

Okay, we need a little more crowd participation up in here.

I propose a new game.

You agree not to use Google or any other electronic search engines to cheat, and I agree not to call you a dirty cheater. You may, of course, dig through your old tapes and records and not-so-old CDs to try to figure it out.

I'll tally points, and every month we'll have a winner(s) of a cheap prize. You'll need to be willing to give up a mailing address to claim your prize.

So the game will be me throwing out a couple lines from a song roughly whenever/as often as I feel like it. Then y'all guess the artist and song title. The first comment with both the correct artist name and song title will win.

Easy-peasy?

Then without further ado, I present May's first (and May first's) edition of Lyrical Pursuit:

I scream my heart out, just to make a dime

And with that dime I bought your love

But now I've changed my mind

Okay, guess away! And you're on your honor not to be a big, fat cheater by Googling it.

UPDATE 6:20 pm--Apparently the Land of Mu and Nu fell down, go boom. But it's back up now! So anyway, I'm sorry some of you already resorted to Google, because since no one has guessed it, I must begin with the clues.

Clue 1: The artist is a hair band (their hair was spectacular), discovered by Jon Bon Jovi, and named for a fairy tale character.

Clue 2: The album was Night Songs.

Clue 3: Yikes. Looks like I should have picked "Don't Know What You Got (Til It's Gone)" as my song. What a fool I am.

Clue 4: Sheesh. Nobody's getting this?

Okay, I think the point system will work like so:

1. Correct answer before any clues are given=5 points.

2. Correct answer after 1st clue given=4 points.

3. Correct answer after 2nd clue given=3 points.

4. Correct answer after 3rd clue given=2 points.

5. Correct answer after 4th clue given=1 points.

6. If no correct answers are submitted, we universally agree I suck at picking songs. Or you suck at figuring clues.

Jew